‘Bearing Witness’ in the Field

28 August 2024

Shahdab Perumal

The sun is merciless in April. I mostly stay at home and spend time with my mother Salma. In some ways, the privilege of doing fieldwork in my village is that it blurs the distinction between home and field. My conversation with my mother blurs that distinction further. Our conversations oscillate between two things. She is increasingly becoming more concerned about me getting married; she usually enumerates and gives me detailed descriptions of all the boys in my village who are already married. She is also equally or more worried about the ongoing genocide in Palestine. She constantly checks her phone and watches all the Malayalam YouTube videos regarding Palestine. She continually worries and prays for the people of Palestine. I also join in her worry and prayer.

My PhD research focuses on identity and inequality in a predominately Muslim-majority coastal village in Malappuram, Kerala. I explore the role of fish stench in maintaining a social boundary between inland and coastal Muslims. I also look at how inland Muslims create and maintain a narrative about ‘smelly’ and ‘unclean’ coastal Muslims. In addition, I attempt to unfold and unpack bordering practices and policing techniques along the coasts and in the ocean. In official and public discourse, the sea is often framed as bringing ‘non-residents’ to India. The Indian state has increased securitization in the sea, especially after a series of attacks in Mumbai on 26 November 2008. For instance, the government has introduced compulsory colour coding for fishing boats, issued Resident Identity Cards (RIC) for coastal village people, and installed radar detectors on the beach. All these make the coast a space of suspicion and scrutiny and implicate the fishing community in the policing of oceans. In my research, I attempt to make sense of the border in the ocean through the lens of these frictions.

Infinite Depths

I wait until evening to leave my home to meet Khalid at the beach. He is an elderly fisherman and my indispensable companion in the field. “Khalid knows infinitely about the ocean”, my friend Sadik declares ever so often – and everyone I know agrees. Such is Khalid’s expertise. I reach the beach, around 10 minutes from home, at 5.30 P.M. Khalid is quietly sitting on the beach near his little boat. He usually keeps a small board on his boat with an instruction: ‘Don’t sit on the boat.’ But the instruction is insufficient to shoo away people from sitting on the boat. And so, he sits near the boat — and the moment someone attempts to sit on the boat, he tells them not to sit. I sit next to him, and then two of us ensure nobody sits on the boat.

On this day, I intend to speak to Khalid about policing in the ocean and ‘anticipated checkpoints’. Even though there is no permanent checkpoint in the ocean, encountering the police is a real possibility. I am curious to know what that does to fishing practices. As is now common, our conversation starts with tea. He always buys me tea, and whenever my nieces accompany me, he buys them ice cream. Over tea, he starts talking about his days in the Gulf and, somehow, we end up having a conversation about which word better describes the ocean: the Malayalam word ‘Kadal’ or the Arabic word ‘Bahr’. He is insistent that the Arabic word Bahr has a “feel” to it; more clearly, that the word Kadal does not fathom the depth of the ocean, but the word Bahr does. I do not argue. Soon after, gossip nourishes our conversation and we discuss the health and illness of the people we know.

As our discussion progresses, we ‘suddenly’ start talking about Palestine at length. He speaks extensively about the Palestinian people and simultaneously curses America and Israel. I tell Khalid that the people of Palestine also engage in fishing practices. He is astonished to hear that, and he begins to describe them as Vambanmar – those who are invincible and powerful.

A friend of Khalid comes to us, greets him effusively, and glances briefly at me. His voice is pedantic. “This is our Ali, Shahdab”, Khalid swiftly introduces him to me. Ali immediately asks me to verify the news he carries from a nearby shop. He has learned that Palestine has fought back, and has caused significant damage to Israel’s army. I follow his curious bidding and google it. It ends up in vain. We do not find any such latest news on the Palestine resistance. The jubilation fades from his face and voice.

Our conversation continues for more than a couple of hours, while we maintain an anxious silence. Occasionally, we fill the silence with the Malayalam words Enthaale (an exclamatory phrase to describe an extraordinary condition) and Padachon Kaakate (May God protect them). Most of the time, I turn my gaze towards the infinite: the ocean. ‘Ocean’ is also often a metaphor to describe the excess or unfathomable. I think about how this metaphorical reading of the ocean finds its truest meaning while we speak about Palestine. We cannot fathom the intensity. Such is its intensity and its immensity.

At around 9pm, I tell Khalid, “I am hungry now. I am leaving.”

“Go in peace!” He replies.

I leave.

As I walk home, I call my friend Leila. She enthusiastically asks me about my fieldwork: ‘did you find something from the field?’ I tell her, as it turns out, we were all speaking about Palestine. A long silence punctuates our call. I try to recollect how we ‘suddenly’ ended up speaking about Palestine. As I reflect, it becomes clear to me that it is never a gigantic jump. It is a very spontaneous and organic transition. It happens all the time, I now realise, even during my conversations with my mother, friends, nieces, and neighbours. Palestine has always appeared in our conversations. I grew up listening to stories about Palestine, like my nieces do now.

In The Shadow of Genocide

We have been in solidarity with Palestine long before Oct 7. Growing up as a Muslim, Palestine is always in our prayers. We all say Ameen, loudly and genuinely, when Ustad prays, ‘Oh Allah, please protect the people of Palestine’ during Ramadan. We also pray for the victims of Iraq, Syria, and Myanmar. But prayer for Palestine is consistent. No Ramadan passes without a prayer for Palestine. It is an interesting coincidence that our life resonates with life in Palestine: united, too, by football and fishing.

Though my research is not about Palestine, it has had an overwhelming impact on how I conduct my fieldwork and everyday life. The question ‘What is the point of doing all of this now?’ dominates my thoughts, profoundly impacting my writing process, readings, and my free time. If I do not “bother” about Palestine and immerse in my ordinary and mundane activity, it leads to another worry about why I am not bothered about Palestine. It is not surprising or unusual that ‘redirection’ happens in the field. Redirection and reorientation, in fact, constitutes ethnographic fieldwork. What we seek to find leads us down other paths. But the conversation about Palestine in the field compels me to ask which of the conversations is a ‘redirection’ from the actual topic. It has become increasingly clear that actual redirection is transgressing from the topic of Palestine. Sometimes I feel as if themes like social boundary-making through fish stench and ocean policing are a kind of redirection from the actual discussion that is Palestine. Especially now.

Though my research is not about Palestine, it has had an overwhelming impact on how I conduct my fieldwork and everyday life. The question ‘What is the point of doing all of this now?’ dominates my thoughts, profoundly impacting my writing process, readings, and my free time. If I do not “bother” about Palestine and immerse in my ordinary and mundane activity, it leads to another worry about why I am not bothered about Palestine. It is not surprising or unusual that ‘redirection’ happens in the field. Redirection and reorientation, in fact, constitutes ethnographic fieldwork.

I spent three months (February to April 2024) revisiting the field, anticipating I would collect substantial notes about life in the ocean, stories related to fish smell, fishing, and the beaches. However, my fieldnotes contain fewer stories on these topics and more and more about Palestine. This pushed me to write about this dilemma in the field. Sometimes, the person I wanted to meet would tell me, ‘Come, let’s go and participate in a protest or solidarity gathering for Palestine.’ The context of how I meet people has changed. How do I even ask specific and sophisticated research questions regarding fish stench, bordering or policing in the ocean while we are out for a protest?

My research is impossible to separate from the fact that I conduct my fieldwork during a genocide that is happening in a place that has long been a part of my world growing up. As such, we are all witness to the indiscriminate and intentional bombing and killing of Palestinians. Anthropologists argue that a researcher’s duty in the field is ‘bearing witness’ or ‘listening.’ When a genocide is underway, the very idea of bearing witness takes on a different meaning. I witness the attempted extinction of a people alongside my participants. I write my thesis with a deep sense of solidarity with the people of Palestine.

Beginnings

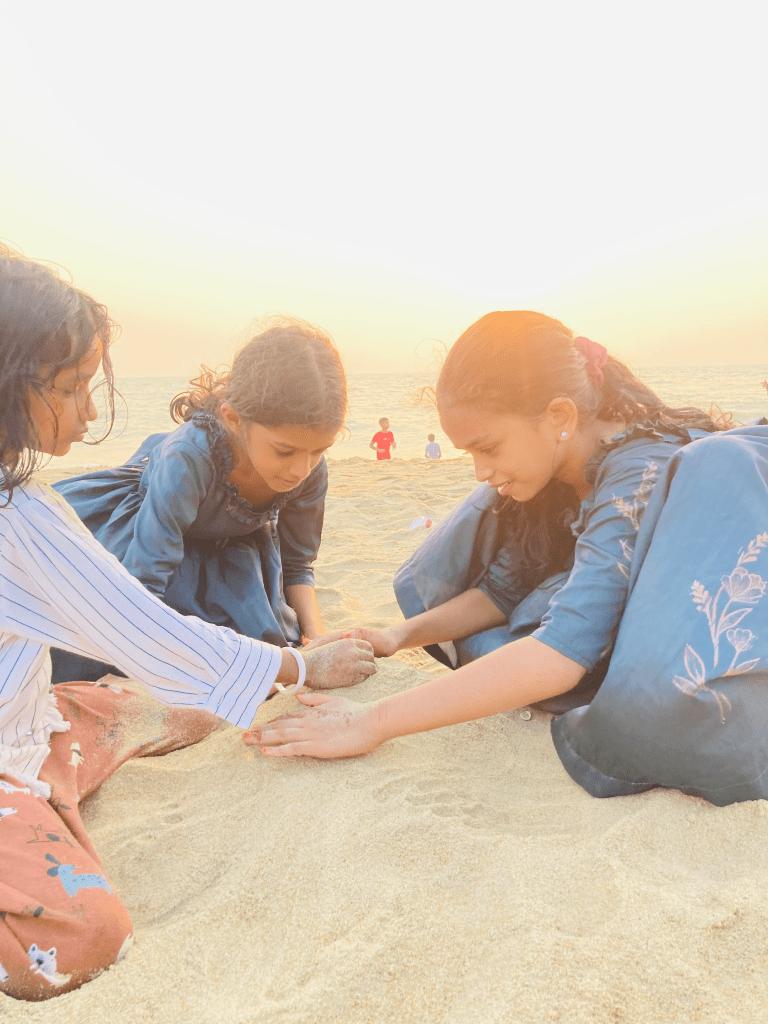

I spend much of my time on the beach for fieldwork; my mother and nieces often accompany me. One day, we decide to drink Cumin Soda on the beach, and my mother spontaneously responds, rather loudly, ‘Who owns Cumin Soda?’ I realise that she wants to make sure that our money is not sponsoring a genocide. I smile. It is the same beach where I conducted my fieldwork with Khalid and others. It is this very place where people have tea, watch the sunset and feel the breeze on their face and in their hair. It is here that children play football and make land art, where fishermen halts their boats. And above all, where people like my mother, Khalid and his friend constantly remind of Palestine, remind me that we are bearing witness, remind of things that matter.

We always keep our hope alive, Inshallah Palestine will be free.

Shahdab Perumal is a PhD researcher in the Department of Social Work at the University of Delhi. You can find Shahdab on Twitter @shahdabperumal.

Reflections anthropology ethnography India palestine reflexivity writing