On Loving A Hostile City

October 9 2023

Medha V.

It was 2am when I got home that day. We — a group of women, all strangers to each other — had walked up and down Nelson Mandela road, a distance of over 6 kilometres. I had met them virtually a week ago, thanks to my Instagram algorithm which led me to a page that organises midnight walks for women in Delhi. The idea of a no-agenda walk in the city with strangers (only womxn) had sounded appealing to me then. But when I woke up the next day, I felt a dull ache coursing through my entire body. I never left my bed and took many long naps that day.

“I don’t think I love Delhi in the same way anymore,” I had told a friend a few months ago, as I broke down in front of her.

Out of all the places I had lived in, this was one city that instantly drew me into itself. It was so alien, so new that I knew that there was this perpetual risk of never feeling fully at home here ever. This was not a particularly uncomfortable feeling for me, though. I had realised very early on that this is a city that only knew how to unsettle: be it with the casual flashes of violence I saw in young boys playing with real guns in the narrow streets of a South Delhi neighbourhood to moments of utter beauty that caught me the first time I saw how the slightly slant, soft winter sunlight fell on the ornate walls of a sixteenth century Mughal tomb.

It is where I realised that history exists not just in the old, but also the new. And if there’s no trace, no acknowledgement, no story, not even a myth about what a place once was; it can often mean that it’s been deliberately forgotten, erased from memory.

We were eight women, all strangers to each other. There was a girl who had sneaked out of her hostel past curfew hour. There was another whose parents didn’t know. There were two girls who had just discovered that they grew up in the same small town. I remembered I had walked along the same road once before, around the same time a year ago, with a man I’d met on a dating app. We shared a meal together at a Naga restaurant and then walked a little to get a drink at a bar nearby. Apparently there’s an entrance to Sanjay Van, one of the city’s many sprawling reserved forests, around here. You can see the aravali mountain ranges from there, he told me. We never went. One of the girls told us she grew up around the area. She had seen the road swell up from just a narrow lane flanked by the aravalis and the jungle, to the massive beast that it is today. It is now a national highway, dotted by shopping malls and a cycling path that ends abruptly. It is lined with imported palm trees that look like they don’t belong, but were just implanted there because someone decided this is going to be the city’s new aesthetic now. In their supposed new home, they looked all shrivelled up, most of them dying a slow death.

Unlike my very first home in Delhi, my current home in this place called Saidulajab, has a window and access to a common balcony. Lots of sunlight was really the only criteria I had while looking to move. (I have a friend who can’t live without thick, blackout curtains. But I hate being insulated from the outside world that way. If it’s raining outside, I need to be able to feel it even without opening the windows or looking out the door.)

Saidulajab is in the Delhi government’s list of “unauthorised colonies inhabited by affluent section of society.” There are around 1700 unauthorised colonies in Delhi, and they mostly sprang up on agricultural land (considered rural land by the government) which is not designated for residential use. They are home to both the working poor and elite nuclear families alike, and Saidulajab has a mix of both.

Basically, this means that I have quick access to a ₹30 chhole kulche breakfast and at the same time can also walk for 400 meters to work out of a café which sells one coffee for ₹276. In my over two years of living in Saidulajab, I have seen that every establishment here—shops, cafes, buildings, coaching centres—gets built, demolished and rebuilt so easily. It feels like this is one of those places where Delhi’s rich put their money in, if they feel like they’re up for an experiment. If it doesn’t work, no big deal — you just shut shop and move on to the next thing.

This sort of impermanence unsettles me to no end. In Chalakudy, the Kerala small town I grew up in, these things rarely ever change. The tea shops and roadside thattu kadas where the men ate and drank, the schools, cinema halls, textile shops: nothing changes. And if it does, the loss of that establishment is mourned over for times to come. Or at the very least, its presence is remembered by people long after it’s gone.

Oh, how good were those beetroot cutlets from Indian Coffee House, such a shame they have moved from Railway Station Road! Vanchi maaman (uncle) has shut down his vegetarian restaurant near the highway: competition from the new shawarma-mandhi shop next door? Remember how good the dresses were at Shobha Silks in North Junction? And so it goes…

I don’t care much for this romanticisation of an idyllic permanence, but I’ll be lying if I say that the rate at which this change happens doesn’t scare me. This has a lot to do with the rate at which money flows, of course. But what really confuses me is how this constant building and rebuilding in and around Saidulajab has made the area, and particularly the experience of it, so…erratic. There are these islands filled with craft coffee, jazzy music, kombucha, and just general south Delhi’ness — but you can’t walk back home after dark because the street right outside is unsafe. It is where the stray cars and Omnis (with the angry Hanuman stickers and caste markers like Jai Brahman/ Proud Jatt/Gurjar) come to sleep. The barely lit road and those empty cars parked along the side give me an eerie feeling. Also, my housemate once got groped there by a boy half her age.

For women, even for privileged women like us, walking alongside a highway at midnight is an event. It shouldn’t be, but it is.

I never even realised how absurd this whole thing is, until my brother came to stay with me for a month. We used to do a lot of things together at the time, and enjoyed being adults together in the same city. We both love walking equally, so we would walk back home from the closest metro station after a movie or a meal no matter what time of night it was. I was overjoyed at the mere existence of that choice to walk. I didn’t make much of it earlier because I didn’t mind paying for a cab or an auto, but that month of walking with my brother really made me rethink many things. What does safety really mean, in a city like this? Is safety the same as money?

The woman who organises the thing told me that men often DM her on Instagram asking what goes on in these walks. She doesn’t entertain these queries, she said, even when they’re asked in good faith. For women, even for privileged women like us, walking alongside a highway at midnight is an event. It shouldn’t be, but it is.

I remember this one evening as I was walking around Okhla with a male friend, he suddenly turned into a dark alleyway. I was startled at how casually he took that turn, while my brain and body froze even though I was in the company of someone I trusted deeply. With every path we don’t take, how many sights, sounds, smells and sensations do we miss out on?

My body knows how to absorb these shocks and quickly bounce back to its default setting now. But I am sure our systems store these things somewhere. What happens to these memories? Will my body ever learn to let go of them?

Several men followed us as we walked, some with their bikes and cars and some with their gazes. Well-meaning auto drivers asked us if we needed a ride. Cars and bikes stopped by the road, and eventually drove away as we walked past them. Even a government bus stopped, supposedly for us. My back stiffened and my jaws clenched every time something like this happened, a danger siren blaring through me.

There were several stretches with security guards, all of whom looked at us funny. Oddly, one time where I felt safe was while walking along an area frequented for sex workers on the lookout for clients.

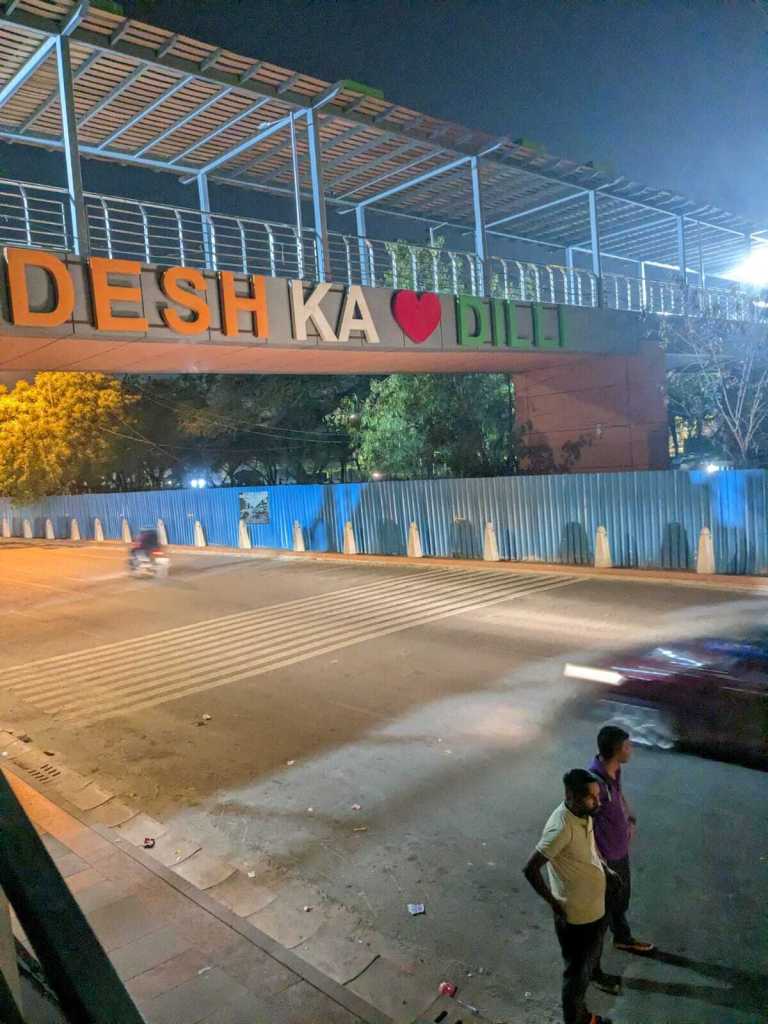

No one seemed to get the fact that we were there to simply walk: slowly, mindfully, with no real intent or destination. And so we walked, along foot over bridges and sidewalks lit by incandescent bulbs, under the shade of trees and long dark patches lined with shrubs and bushes, past huge hoardings with photos of men who head the country’s government obscuring the night sky.

I need my involvement with a city to always be intense, volatile, and at times aggressive, much like the relationship I share with a friend, sister, lover. I get restless and insecure every time I sense a lull in this intensity. How do you know if you’ve stopped loving a city like you used to? I think one definite sign is when your favourite routine feels truly mundane.

My body knows how to absorb these shocks and quickly bounce back to its default setting now. But I am sure our systems store these things somewhere. What happens to these memories? Will my body ever learn to let go of them?

I felt it a few weeks ago, as I was doing my usual rounds in South Delhi’s Malviya Nagar market. It is very close to my first ever home in Delhi, where I lived for about a year. I’d go to the market every other day when I lived there. I remember being drawn to the chaos of the place, and found myself relating to the largely middle-class crowd that frequented the shops there. It is where I learnt that it is possible to find pockets of safety and warmth, in a completely new city that spoke an alien tongue.

So, I continued to go there even after I moved from the area. And over the years, I have made friends with the guy at the alcohol shop who always smiles at me and lets me skip the queue. I talk politics with the man who sells saag in the sabzi market. I pet the ginger cat at the chai stall and buy seasonal flowers from the same old woman. I know that the grumpy uncle at the grocery store has an identical twin. And when I stop by to drink an overly priced filter coffee from the nearby Sagar Ratna (which, as a friend put it, is the McDonald’s-equivalent for South Indian food), the man there lets me have the bigger sofa even when the place is packed.

This routine used to be the fuel that gets me through the rest of the week, but it just didn’t feel the same the last time I was there. This left me with a sinking feeling. Have I been here too long? Is it time I leave Delhi? I sorely wished I’d loved the city in the same way again.

I matched pace with the girl who sneaked out of her hostel at one point. She was wide-eyed, bespectacled, stiff, alert. It’s her first year in the city, she told me. I was so excited for her. I remember being new to the city, and the specific joy of being amused by the small things. Like the first time I saw the fluorescent lights flashing off the streets of Paharganj, the time I stopped an auto midway and got down to see the Najaf Khan tomb in Lodhi, all those February afternoons spent alone in the neighbourhood park reading a book and eating jhalmuri, coming back to the comfort of your home after a bad date and cooking your favourite meal. So many things!

Girl you’ve no idea how amazing it’s going to be, I thought to myself, as I asked her: Why don’t you just live with a few other girls in a rented apartment? Why do you have to live in a hostel with curfew and all?

“But I feel the hostel is safer,” she told me.

This answer annoyed me. I suggested softly that perhaps she could find nice people to live with.

I wondered if walking along this goddamn national highway in the middle of the night felt safe to her.

Maybe I was being inconsiderate, even in thinking something like that. But it came from a place—a very stubborn place—of wanting to vicariously live through this new girl’s experience of the city. I wanted her to embrace the city in all its complexity, but I also didn’t want her to be naïve. Maybe she will eventually move out of that hostel and host house parties in a rented flat which is warmly lit but has water problems, maybe maybe… Maybe a lot of us don’t realise it, but a woman’s relationship with the city she lives in exists in contradictions.

“This city—I know how it infuriates and enchants you in equal measure,” read a text from a male friend recently and I felt it to be true to my bones.

It is almost as if the city of Delhi is a shapeshifting creature, constantly expanding its reaches, often taking over spaces that were once forest or farmland. But a woman’s experiential map of the city —dictated by patriarchs within their homes and drawn by patriarchs within urban planning boards — is a miserably shrunken version compared to the original one.

There was anger at the unfairness of it all, but there was also joy that night. We stopped to look at trees and flowers, shared some laughs, poetry, silences and snacks. We spoke about the next night walk (the hostel girl volunteered to show us around her area), but no permanent bonds were created. None of us made plans to meet up outside of the walking event. None of us swore to be best friends with each other. We had other lives, friends, homes/hostels, partners and pets to go back to.

But a woman’s experiential map of the city — dictated by patriarchs within their homes and drawn by patriarchs within urban planning boards—is a miserably shrunken version compared to the original one.

We came together guided by our individual IG algorithms, and just trusted each other no questions asked, went on our own intense trips, and as the night ended, dissipated with a beautiful lightness. As for me, this was my earnest attempt to relove the city, in a way that’s stubborn, persistent and—hopeful.

Medha V is an independent editor and writer. She lives in Delhi. Find Medha on X (formerly known as Twitter) at: @medhavenkat