From Dhaka to Oklahoma: Researching at a Distance

26 September 2025

Aishwarya Ahmed

Swarming through a sea of celebrating people at a snail’s pace, we were greeted by strangers banging on the car’s window, shouting the celebratory greetings “Eid Mubarak” and “Happy Independence Day”. It was August 5th, 2024, the day Bangladesh’s authoritarian government fell, and caught between the celebration and chaos on the streets of Dhaka, I was on my way to the airport to return to graduate school in the US. The political upheaval was the result of a mass movement throughout July 2024, that faced violent repression from the authoritarian regime, killing almost a thousand people. Eventually the regime of 16 years collapsed, the fallen Prime Minister fled the country, and celebration erupted. In the middle of the celebrations, members of the mob suspiciously checked every car to see if they carried escaping members of the fallen regime, including ours.

As we waited in the queue, suddenly just ahead the crowd started verbally attacking a female foreigner for not wearing a head covering, the mark of Muslim feminine piety. This prompted my father to rush to the car with a worried look and, for the first time in life, tell me “Cover up quickly”.

Covering up has a religious significance in Islam, but my upbringing was not religious. In the scorching summer heat of 88 °F, I used my scarf to cover up, for survival. This act, performed from fear rather than faith, foreshadowed a different kind of self-imposed covering up I would engage in when I thought about how to address the political upheaval on social media.

Watching the mob behave this way, we were getting tense, at the same time trying to maintain our forced smiles, worrying if the crowd could sense our disdain for their unruly activities. I was worried about my family and comrades and what this political transition meant in the long run. But I had no choice. I had to smile, and I had to leave.

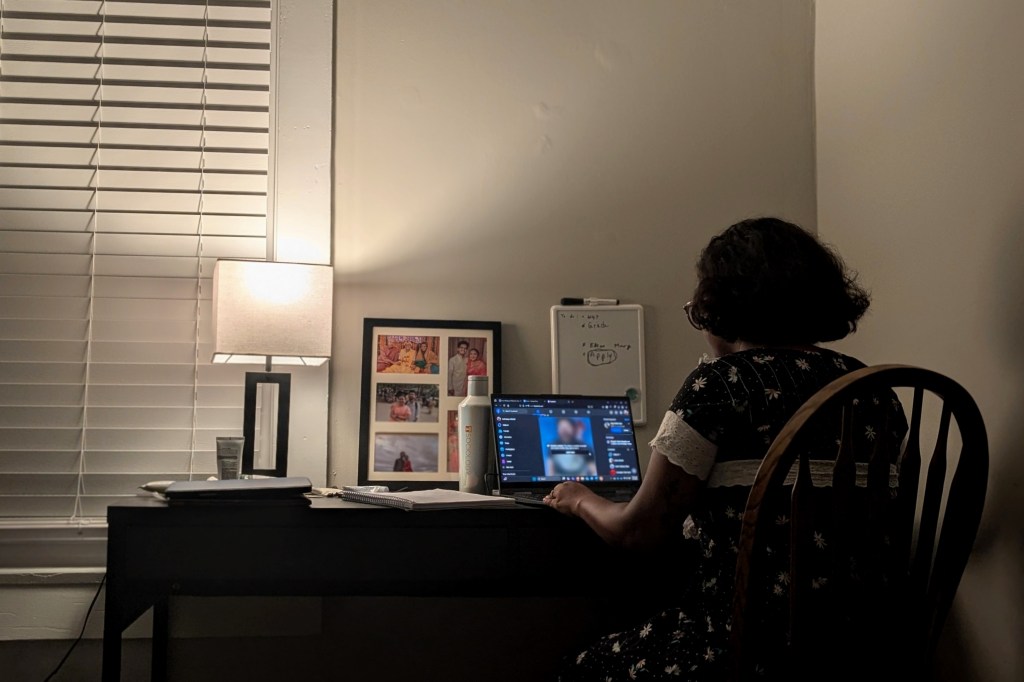

In conducting digital ethnography on my home from afar, I was caught between being here and there- at times drowning in deadlines and other times stuck in a perpetual worry about home and comrades.

A month later, thousands of miles away from home, I started working on my master’s thesis in Oklahoma, tracing the aftermath of the political transition since the fall of the authoritarian regime, through the social media activity of present and former members of Bangladesh Students’ Union, an organization I had belonged to for years. I was studying repression in Bangladesh, from the US, while my comrades in Bangladesh were facing it. In conducting digital ethnography on my home from afar, I was caught between being here and there- at times drowning in deadlines and other times stuck in a perpetual worry about home and comrades.

As a homesick international student whose entire life is halfway around the world, social media is a way of being present, being home for me. I am usually online a lot, looking at serious news from home, and silly posts from friends. And as a consequence I sometimes feel guilty for wasting time. But my new project gave me an excuse to waste my time on social media. I scrolled constantly on Facebook, barely sleeping at times when things back home turned particularly turbulent. I frequently told myself that this was for my thesis, for digital ethnography, but it was not just a tool for my research. It was also a way to engage with my life in Bangladesh, to participate from afar as my country went through the changes. During my higher studies abroad, I have always longed for home- the people and the food. But this time it was not just the distance, it was also the timing. It was because I was on the other side of a screen during a turning point in Bangladesh’s political transition.

Kind of like the quote “there are weeks where decades happen,” it sometimes felt like decades passed in Bangladesh during eight hours of sleep in Oklahoma. Due to the time difference, almost an entire day in Bangladesh was gone, with what felt like thousands of incidents by the time I woke up, feeling dizzy, disoriented, and lost in a sea of a thousand posts. With no clue of what had happened, I would call my comrades, desperately trying to understand the context. As an ethnographer, I tracked the Facebook posts and also behind-the-scenes conversations and incidents. As a political activist, I just worried, got on hour long phone calls, and translated my anger into snippets on Facebook.

Researching my country and organization from thousands of miles away during a political upheaval was a privilege and a burden. Being so far away, I was physically safe, away from the immediate threats of violence. At the same time, I felt like an injured soldier in a hospital, while my comrades were on the battlefield. My safety brought a pang of guilt. While my comrades were out on the street, I was scrolling Facebook for updates, waiting for friends and family to appear online.

While translating my thoughts into status updates on Facebook, with my comrades from Bangladesh, we found ourselves spending more time in our conversations on WhatsApp/Messenger discussing what would be “safe” to say than actually saying it, at times silencing and bypassing the words. Reacting to any offline incident and navigating uncertainty, insecurity and fear, we turned to each other for guidance, and in conversations, decided whether to post or not. When we decided to post, we would edit our drafts based on the advice and suggestions from the conversations, before publishing the post. Our frequent conversations about the word choices and even whether to upload statuses or not, made me aware of the strange, constant, collective self-censorship, and prompted me to explore it in a turbulent political landscape for my thesis project. This collective nature of self-censorship became the focus of my fieldwork. It illustrated how repression dictates our social media activity, revealing how, in a climate of fear and political uncertainty and instability, members of a tight knit network shape and censor their posts through a social and collective process. Lucky for me, I already knew my participants. They were my friends, comrades from struggles past. Uploading Facebook statuses was not only a part of our individual thoughts and expression, but a channel for activism for the organization. Through social media updates, the organization gets the message out to the people, setting their narratives, and protesting online- which kept me tethered to my comrades at home in this violent rollercoaster ride of events.

From thousands of miles away, studying my country in a turbulent political landscape was not just a matter of academic curiosity. It was my way of participating in the political process from afar- by posting and protesting with my comrades online. I talk a lot about the distance- but despite the physical separation, I was immersed in the struggle, in the fear, in the conversations, in the silences, as digital ethnography kept me connected.

After the fall of the authoritarian regime, the mob turned vengeful. People started targeting repressive forces, religious minorities, and symbols associated with the previous regime, including sculptures representing the Liberation war of 1971. When these attacks were happening, all I could do was to keep field notes. In a space where my comrades were actively participating in one way or another, I was taking notes. I was tired, anxious, angry, helpless, but again, taking notes. As a political organization, they were fighting the fight on how to proceed in the new political terrain, and I was datafying the experiences. That’s all I could do. At one point, I started accepting a meme that often resurfaced on Instagram: “terrible country, but incredible meme content”- though in my case it was “incredible research content”. The more turbulent the situation became, the more data it offered. Such a cruel irony. But in a way, this became the way I could engage with Bangladesh, by studying it. Research became my bridge to my home country.

From thousands of miles away, studying my country in a turbulent political landscape was not just a matter of academic curiosity. It was my way of participating in the political process from afar- by posting and protesting with my comrades online. I talk a lot about the distance- but despite the physical separation, I was immersed in the struggle, in the fear, in the conversations, in the silences, as digital ethnography kept me connected. In the end, political engagement and activism are not confined by borders, repression can transcend boundaries and of course, ethnography can be shaped by distance.

Aishwarya is a PhD student in Sociology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, focusing on Political Economy and Globalization, while juggling life, activism, and academia.

digital ethnography Methodology Reflections social movements