(Un)knowing the Sea

17 August 2025

Indu Poornima

I thought I knew the sea …

The sea disciplines itself into a rhythmic tranquillity, insisting that I let go of the unforgiving cacophony in my head. Occasionally, it would send lost belongings, floating on its waters, for me to find. I kept some — they claimed space in the baggage I carried across time and cities.

Often, with unabashed melodrama, I’d think of myself as the chosen one: “The sea thought I’d be best suited to bury this dead starfish, bid it a dignified farewell.”

Last year, when I found myself committing to study the Kerala coasts for my PhD, I wanted to extend the same theatrical narrative — ‘the sea brought the topic to me’. Except, it didn’t. Instead, lack of funds limited my field choices to a language and geography I was familiar with, where I could stay at my parents’ and not exhaust my monthly stipend doing fieldwork. Eventually, my research questions took shape, and I decided to explore the socio-political transformations from introducing large infrastructural projects, such as transhipment ports, in Kerala’s coasts.

I soon realised what stood between me and the ethnographers who traversed cultures, spaces, risky paths and acclimatisation techniques they used in becoming the insider was also money, amongst other things.

At the coasts, I am already an insider … right? Because, of course, I know the sea.

After all, I grew up less than 5 kilometres from the coast. I religiously went to the sea to feel chosen; could easily name at least 10 fish varieties off the top of my head; knew the tricks to pick the freshest ones from the market; could make, eat and enjoy sumptuous seafood delicacies. For most of my school days, I travelled with fish-selling women in public buses, peeping into their baskets to see how good their business was for the day.

I really thought I knew the sea and its people.

It took only a few days of my pilot study for the thought to change irrevocably.

The difference those few kilometres made between coastal life and the one I had as an inlander was gaping. The sea you see as a visitor is different from the one you derive your livelihood from. I was a guest, a friendly neighbour at best. Guest privileges immunise you from the unpalatable.

The rhythmic tranquillity gives way to clamouring auctions of fresh catch at four in the morning, if not earlier. Local sellers and middlemen vie for the best price, occasionally breaking into squabbles. The irresistible aroma of a sizzling karimeen fry or fish moliee begins its journey from the heaps of fish dumped from boats onto wooden slabs, to be auctioned and carried in colourful, plastic containers. All in a harbour where the smell of fresh catch mixes with the stench of the rotten, waiting to be processed and used as animal feed.

The difference those few kilometres made between coastal life and the one I had as an inlander was gaping. The sea you see as a visitor is different from the one you derive your livelihood from. I was a guest, a friendly neighbour at best. Guest privileges immunise you from the unpalatable.

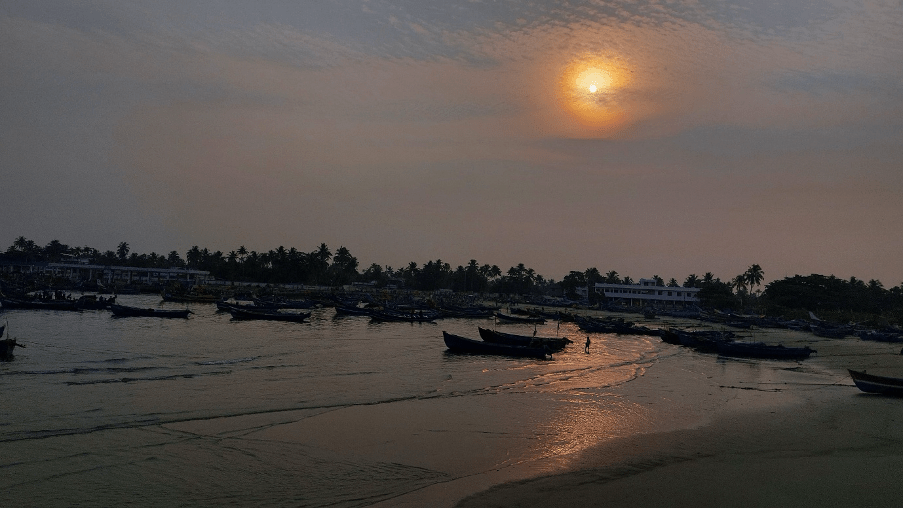

The photo series is taken from my fieldwork in central Kerala, as I try to learn, unlearn and relearn the sea, as an outsider. I use the images to contrast the space, colours and noise of two fishing harbours. The first at Thoppumbady, run by the Cochin Port Trust, is modernised, strictly monitored, and one of the largest harbours in the country in terms of area. A few kilometres away lies Chellanam, bustling with locals, openly accessible for anybody fancying a visit. Unlike at Thoppumbody, where a good share of the catch is sent to export processing units, Chellanam caters to its local buyers.

Thoppumbady

The photo series is taken from my fieldwork in central Kerala, as I try to learn, unlearn and relearn the sea, as an outsider. I use the images to contrast the space, colours and noise of two fishing harbours. The first at Thoppumbady, run by the Cochin Port Trust, is modernised, strictly monitored, and one of the largest harbours in the country in terms of area. A few kilometres away lies Chellanam, bustling with locals, openly accessible for anybody fancying a visit. Unlike at Thoppumbody, where a good share of the catch is sent to export processing units, Chellanam caters to its local buyers.

CHELLANAM

Boats rest after a busy morning. I sit beside them talking to Allen, my interlocutor and a youngster from the fishing community. ‘It will most likely rain in an hour or so… you can borrow an umbrella when you leave.’ Instinctively, I glance at my phone for weather updates that assure it is a sunny day.

“You don’t believe me.” Allen smiles. “I wouldn’t blame you… Most inlanders would consider the weather app to be more scientific than the knowledge fishers have from their lived experiences of the sea.

When you’ve been packing your belongings and moving to a relative’s house or the (relief) camp every monsoon as the water engulfs your home, you develop the ability to know it in your bones when rains are on their way.”

I sheepishly mutter an apology. It is in moments like these in the field that my positionality makes a candid appearance, as a reminder of the guest privileges I embody as an outsider. For instance, I have the choice to avoid fieldwork during the monsoon months, when the Kerala coasts are prone to flooding. But those whose identities and livelihoods are tied to the sea do not have such luxuries- they wade through the murky waters to get on with their everyday.

I, for one, am yet to return his umbrella.

1 All names used in the essay are pseudonyms.

2 Typically, among fishing communities across Kerala, only men go to the deep sea for fishing. Women stay onshore, engaging in allied activities such as fish vending and drying of leftover fish, which forms their primary source of livelihood. Sometimes older men, after having retired from deep-sea fishing, also become fish-sellers in the neighbourhood.

Indu is doing her PhD in public policy at the Indian Institute of Management, Bengaluru. She studies the political economy of development in the context of coastal communities of Kerala and is currently doing her fieldwork. She is also trying to learn how to swim, both physically and within academia, with some success in the former.

creative narrative nonfiction Methodology photo essay reflections visual-ethnography coasts fishing India labour Methodology